The below is a slightly abridged and edited version of Chapter 1 from my book The Thinking Person’s Guide to Fitness

~

What Is Fitness?

Before taking any new steps to become more fit, it’s worth first taking a step back and considering things from a broader perspective. Why do we want to get fit? Are you already fit? If not, why? Do you want to be fit, or do you want to be healthy? What does “fitness” even mean? Being able to answer these kinds of questions will help point your fitness efforts in the best possible direction.

Health & Fitness

While not synonymous with fitness, “health” is a word that often goes alongside it. This book, for example, is probably classified under a “health and fitness” category. Since they are so frequently placed together, we should first separate them conceptually to clarify their differences and similarities.

Health

Health is usually defined in a “negative” way: as the absence of illness or injury. So one way to think of the difference between health is fitness is that health is about fixing problems and fitness is about increasing capabilities.

Despite this important difference, though, health and fitness do share a lot of similarities and are indeed closely related. For one thing, both health and fitness are gradations, rather than binary states. You can be more or less fit, and more or less healthy, but there isn’t really an overall state of perfect health or perfect fitness, nor — barring death — perfect unfitness or unhealthiness

Likewise, changes in health and fitness are related to each other, often causally: making yourself healthier will usually make you at least a little bit more fit, and making yourself more physically fit will — unless you go to an extreme — also make you healthier.

This book focuses on fitness, with the idea that increases in health will follow.

One reason for my focus on fitness is that it is far more within your control. Anyone can increase their fitness with smart exercise and good nutrition. And while some preventative measures can help keep you healthy, they tend to be things you shouldn’t do (smoke, binge drink, rub your face after riding the subway, etc). Moreover, most of the really critical things that will affect your health are due to the roulette wheel of life. No matter how many precautions you take, the flu can still get you, along with all kinds of different diseases and disorders.

The focus of this book is on those positive things that we can control to increase our fitness. The benefits to your health — and there will be many — are simply along for the ride.

So let’s give fitness itself some detailed thought. How we define it will make a world of difference in the specific practices that will help achieve it.

Fitness

From a scientific perspective — at least since Darwin published Origin of the Species some 150 years ago — we tend to think of fitness in its evolutionary sense. This definition equates fitness with the ability to survive long enough to reproduce and pass on genes to a new generation. It’s the notion of “survival of the fittest,” via the forces of natural and sexual selection. But this technical definition does not really help much in any practical way: after all, from a purely genetic and evolutionary perspective, once you’ve had and raised your kids, there’s not much point in continuing your existence, much less staying active and happy in your body.

The word “fitness,” though, is a form of the thousand-year old word “fit.” And so the technical, scientific sense in which biologists think of fitness today derives from a deeper and older sense of fitness. This type of fitness means to be adapted or suited to something.

You can think of “fitness” in a very literal, spatial sense. Does the peg fit in the hole? Do those pants fit you? How many things can we fit into this box?

Alternatively, you can think of fitness in the sense of something being suited to a particular purpose. Does this tool fit our needs? Is this food fit for human consumption? This sense of purposefulness also relates to ways in which we often use the word in relation to ourselves or other people: in the sense of skills and capacities to do something. For example: he was fit for battle; I wasn’t fit to do anything after drinking all night.

When we refer to physical fitness, we sometimes do so in the spatial sense mentioned above: being “in shape” or “out of shape.” But those phrases are typically less about the physical form we have than about the broader sense of being able to do things — through specific skills, through raw strength or speed, or through a general robustness and capability to withstand stress without injury.

Practically speaking, being physically “fit” means being able to go about your daily life with minimal stress: ordinary tasks shouldn’t seem effortful, you shouldn’t be exhausted at the end of a normal day, and you shouldn’t need to avoid certain common tasks because of a lack of physical ability. That’s a very basic form of fitness, and one in which we should all be interested.

There is, though, a slightly more ambitious level of physical fitness that I think is important for almost everyone to strive for: preparedness for the occasional big stressor. It’s nice to be able to carry a big load of groceries to your car, but if something happens and you need to carry a child a half mile, being able to do so will turn out to be far more important. Similarly, being able to walk around a new city all day while on vacation is very nice, but being able to run incredibly fast for a few minutes might one day be crucial. Fitness in this sense — of being not just capable of dealing with normal circumstances, but also capable of dealing with an emergency situation if need be — ties back into the evolutionary definition of fitness first mentioned, in that it could keep you alive.

Goals & Environment

Given the above, I think that we can now define basic fitness as “being capable of going about daily activities with ease and being prepared for the occasional emergency situation.” That’s a good definition for human physical fitness, and it works well with the more general definition of fitness as “adapted to a specific task in a certain environment.”

Note that there are two important ideas embedded in this general definition of fitness. First, there is a task or goal of some sort, a purpose by which individual fitness can be gauged. Second, there is something which is being adapted to: this implies an outside world, an environment. These twin ideas of a goal and an environment each have incredibly important implications as you go about trying to become more fit.

Goals

The first implication relates to your goal. Really understanding your personal fitness goal (or goals) is essential, and sets the parameters for what fitness will mean for you. For most of us, the definition I provided above — “being capable of going about daily activities with ease and being prepared for occasional emergency situations” — is perfectly fine, and the majority of the advice in this book is based on meeting that goal. But it’s worthwhile to give some additional thought to the question of your overall goal, and/or any specific goals you might have. Awareness of these will help you adjust my advice to fit your own personal needs. Being fit isn’t necessarily the same for everyone.

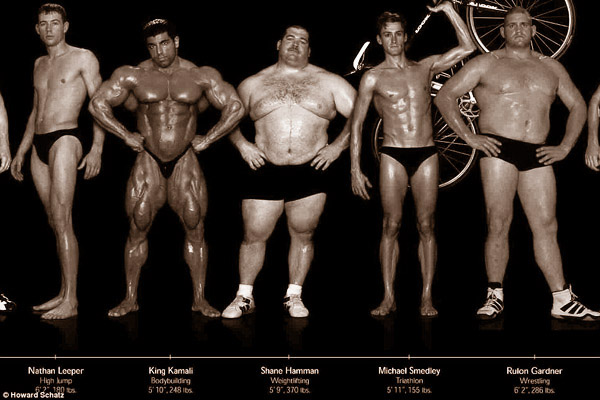

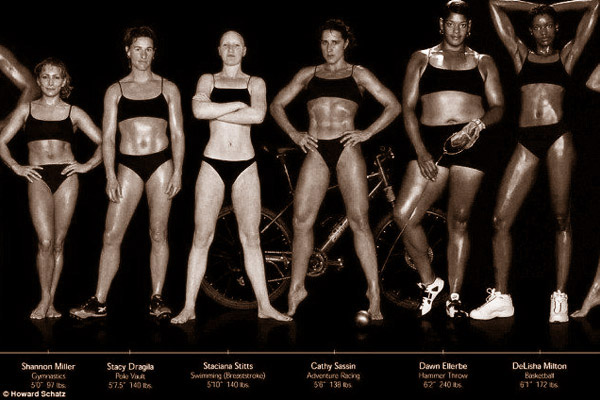

Photographer Howard Schatz provides a wonderful example of how fitness can be completely different for different people. In a series of 125 portraits of champion athletes he made some fifteen years ago, he examines the literal notion of being “in shape.” I’ve reproduced samples of some of these below, but it is worth doing some image searches online and viewing all of them. These are perfect illustrations of how the expression of a person’s fitness changes based on their goals.

We tend to have an image of a “fit person” as someone who looks more or less in some sort of ideal “shape” like Michelangelo’s David. But the reality is that how a really fit person looks is actually a result of what they are making themselves fit to do. And when one specializes in doing just a few very specific things very well (which is what any champion athlete does), their body will adapt to those needs. The body of a power lifter is necessarily different from the body of a marathon runner; for that matter, even a sprinter will have a different body from that of the marathoner.

Swimmers, wrestlers, cyclists, rock climbers — they all develop very different bodies. Who is the most fit? Asking this presupposes the question, fit for what? Schatz’s photos do a good job of illustrating the importance that your goals play in creating the physical form your fitness takes, and how specialized goals and specialized forms of training will lead to very specific (and very different) body types. They are also good, I hope, at illustrating that your body can take on all kinds of different shapes and still be fit.

While there’s a danger that some people may use the “body acceptance” movement to justify a lack of discipline and inability to walk up a flight of stairs without getting winded, the basic idea behind body acceptance is spot on, and an important corrective to the constant photos of similar-looking models and actors we all see every day. There really isn’t any single ideal form your body should be: what is important is that you are capable of doing what you want to do.

Another thing these photos illustrate is that body transformations result from the process of becoming fit. Except for the bodybuilders, no one in those photos set out to look the way they look. Rather, they set out to become very good at a specific activity, and the process of achieving that difficult goal transformed their body’s physical form. This is the way you should think about your own fitness.

I understand that appearance is an important aspect of fitness for most people, and there is nothing inherently wrong with that. But appearance will change very slowly, and is only alterable in certain respects: a higher fitness level won’t do anything about your receding hairline or big ears (just to name two things I can’t do much about).

Instead of trying to make yourself look a certain way, you’ll be better served to focus on making your nutrition wholesome and increasing various physical abilities. Take your cue from the architect Louis Sullivan: “form follows function” — work on how your body functions, and form will follow.

Environment

Your goals aren’t the only factor that shape your fitness levels and your body’s form. Neither you nor your goals exist in a vacuum. In fact, the outside world — your environment — shapes your form as much as your goals. While we can use Howard Schatz’s photo series as a way to see how different goals create a variety of different forms, we can also use them to focus on the similarities between all of these humans.

This brings us back to the evolutionary sense of fitness at the start of this chapter. While athletes may reshape their own bodies to become better at specific tasks within the specific environment of their sport, they are still all working with the same basic human blueprint, one which has developed over millions of years to be suited to the task of surviving and reproducing on the planet Earth. And in the sense that (almost) all of us have two arms and two legs, and can walk and talk and so on, we are all fairly well-suited to the primary forces in our environment.

This makes sense, of course. The forces of evolution “designed” us to be able to resist gravity, move around, communicate, etc. In its slow, plodding way, evolution creates creatures that are perfectly and naturally suited to their environments. Highly unfit beings die off before they reproduce, and all species of living organisms slowly — over the course of hundreds and thousands of generations — become more and more fit, at least with respect to the environment in which they evolved.

But what happens when the environment you find yourself in is not the one you were designed for? The answer to this question is the key to understanding why there is a fitness crisis (and obesity crisis, and health crisis) in the modern world.